I’ll start with some local conditions chat, then get to the discussion. Two weeks ago here in New England, we got 3″ (about 8 cm) of snow, but since then we’ve had days where the temperature reached as much as 80 degrees F (27 C) — and it has rained. My backyard has jungle-ified to the extent that while working back there this morning, you could feel the flora breathing with the humidity. (I already have had to deploy the chainsaw to free some trees of vines.) My wife is also doing hand-to-paw combat with the chipmunk colonies. In short, spring is here.

I’ll start with some local conditions chat, then get to the discussion. Two weeks ago here in New England, we got 3″ (about 8 cm) of snow, but since then we’ve had days where the temperature reached as much as 80 degrees F (27 C) — and it has rained. My backyard has jungle-ified to the extent that while working back there this morning, you could feel the flora breathing with the humidity. (I already have had to deploy the chainsaw to free some trees of vines.) My wife is also doing hand-to-paw combat with the chipmunk colonies. In short, spring is here.

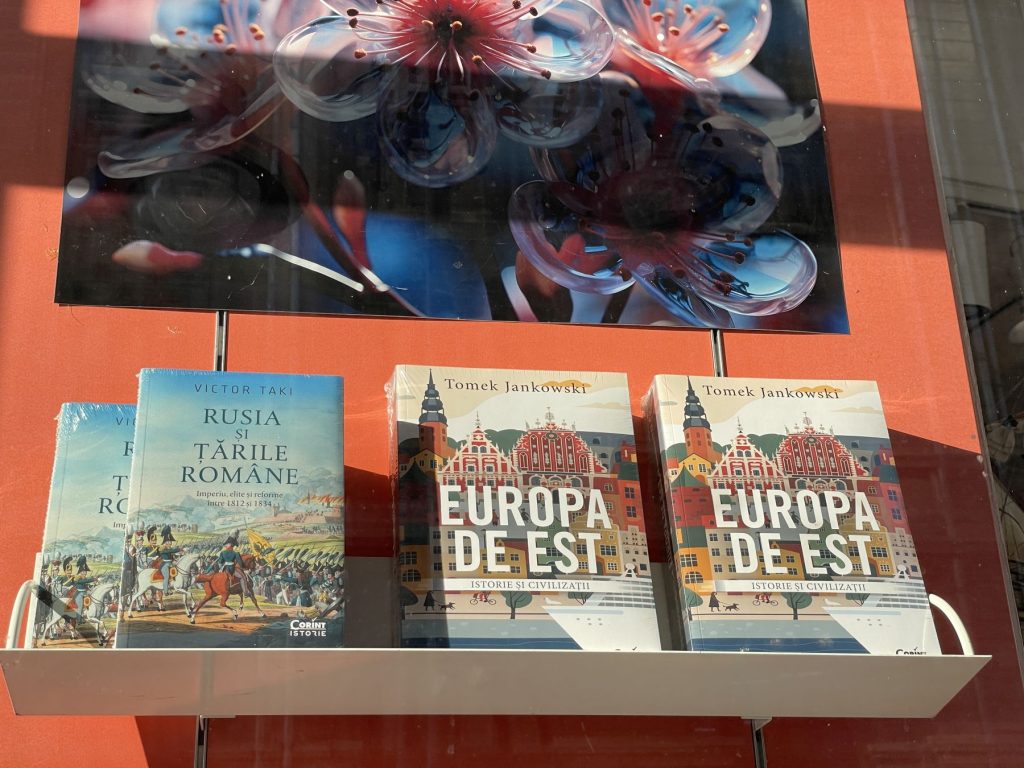

So, the confession: I personally witnessed the last years of the communist regimes in Eastern Europe, especially Poland, Hungary, and Romania. I had the honor to meet and befriend people who were risking a lot — in some cases, everything — to challenge the regimes, and eventually to bring them down. I knew people who had been imprisoned, and even those who had lost family in the 1950s, the disappeared. I both witnessed and heard all sorts of amazing stories of human resilience in the face of oppression, of astounding bravery that will inspire me for the rest of my life. One family in Transylvania took the extreme risk of sheltering my idiot self and a Hungarian friend in the waning days of the Romanian Revolution, housing and feeding us for a week until trains re-started and we could return to Hungary.

And I also had the satisfaction of seeing those brave people win, of watching those regimes crumble and fall. In my home (university) city in the early 1990s, there was a back-street club called the Klub Denevér (“the Bat Club”) where washed-up old communist cronies who had once owned the city went to drown their sorrows. I saw people empowered, finally able to speak freely and have a say in their country’s future. They were full citizens again. I can’t begin to describe the energy.

(Panie Lechu, jeśli to czytasz, byłem w tłumie zgromadzonym przed Zamkiem Królewskim w dniu Twojej inauguracji prezydenckiej w 1990 r.)

I participated in some very minor, symbolic stuff. My Hungarian teacher conducted classes while we hung opposition posters after dark, skulking between alleys and watching for police. Again, minor stuff like that. But a key difference I was aware of even then was that for whatever I was risking, it was nothing compared to the local people beside me. Most of my family had left the region decades ago and so whatever consequences I incurred only impacted me. My friends in Warsaw or Pécs, however, were also risking the livelihoods of their family and friends. My family was safe, thousands of miles (km) away, from the clutches of despots and their police cronies, the SB or ÁVH.

And therein lies the problem. [Here comes the confession part.] I came to realize how much of an American mindset I’d had as I witnessed events. It was more than just an American perspective, which would be fine, but a very American sense of…separateness. Of detachment. This became more evident some years later as people like Vladimír Mečiar in Slovakia, Aleksandar Vučić in Serbia, or Viktor Orbán in Hungary each achieved power through democratic means but then began to subvert democratic institutions in their respective countries. And usually, with at least some element of popular local support. I kept channels open with friends resisting these milder, “authoritarian-lite” regimes, usually less because of left-right politics than simply because they saw burgeoning dictators being born. The stakes weren’t as high as the 1980s…or were they? Again, some amazing people stood up to these regimes, and continue to.

But a key ingredient in my thought process about these events was that they were strictly local events. Orbán was a reflection of some very Hungarian historical politics and trends, including — to be brutally honest — Hungary’s weaker history with democracy. With such a short runway of democratic institutions and legitimacy, should anyone be surprised that an opportunist like Orbán could come along and invoke older political ideals of the 1930s and 40s that still resonate among some Hungarians, especially those who have seen fewer benefits of the post-1990 era? The flip side of that thought process in my mind was the (let’s be honest, smug) notion that something like that couldn’t possibly happen here in the U.S. American democratic institutions (to varying degrees) go back 238 years and have survived innumerable tests, including a civil war. Surely the problems that plague the ~30 year-old Eastern European democracies couldn’t possibly put a dent in the American colossus…could they?

It’s not just that I was wrong about that latter point. It is happening here, in slow motion, but just as surely. There were some American writers like Sinclair Lewis who wrote about this potential back in the 1940s, but it all seemed like quaint hyperbole to me. Until now. Political pundit George Will once argued against erecting a monument to World War II veterans in Washington DC by saying, just stand on the National Mall and look around. What do you see? You see the FDR Memorial, the Jefferson Memorial, the Lincoln Memorial, the Washington Monument, etc. These are all testaments to American values, the very values World War II veterans helped preserve so effectively through their tremendous efforts and sacrifices.

And now, someone wants to hold a Soviet-style military parade very akin to the traditional Great October Revolution Parades in front of the Lenin Mausoleum in Moscow right smack through the National Mall in Washington.

OK, so this blog is not about American politics and I will cease and desist my whining immediately. Though, as a parting shot, I will mention that I now wonder: will I be called upon to summon up the same bravery that my friends, classmates, and colleagues did 30 years ago in Eastern Europe?

But more to the point. This realization that the U.S. itself, despite its long record and history, is as susceptible to the siren song of magic man-ism has also forced me to do a couple things.

One is to force down a slice of humble pie as I speak with friends in places like Hungary, and apologize for any past arrogance on my part. Indeed, as one friend noted to me this morning with some Schadenfreude, some of the American political elites currently bulldozing American democracy are actually in thrall with Orbán, his regime, and the tactics that help him retain a stranglehold on Hungary. Some here in the U.S. see that as a blueprint. So, mea culpa time. Turns out what was good for the goose really was good for the gander as well.

But as importantly, this whole experience of watching my country slide down an authoritarian hole — with the eager blessing of at least some of my fellow Americans! — has at least given me the perspective to rethink and reexamine how I’ve approached Eastern European and world history. It has already provided some new lens into, for instance, the crumbling of the Weimar regime. Oddly, I used to argue for this kind of perspective when examining Poland during the war, for instance, arguing that Poland’s experience should be seen as a case study for what happens when a country is occupied and brutally suppressed; how do individual citizens behave when there are no more official institutions to provide guidance or legal guard rails, when all social mores break down? But I did not extend that thought process as strongly as I should have to other places and peoples. Authors like Peter Ross Range, Christian Goeschel, Laurence Rees, Richard Evans, Timothy Ryback, and Andrew Nagorski were all in my library, but bear re-reading — with new eyes.

And so, if anything, this experience is making me a better historian, and hopefully a better person. (My wife gets final vote on that latter part.) It has added greater weight and empathy in my mind for those peoples — whatever their beliefs — going through turmoil and institutional collapse while extremists lay waste to their societies.

Be well.

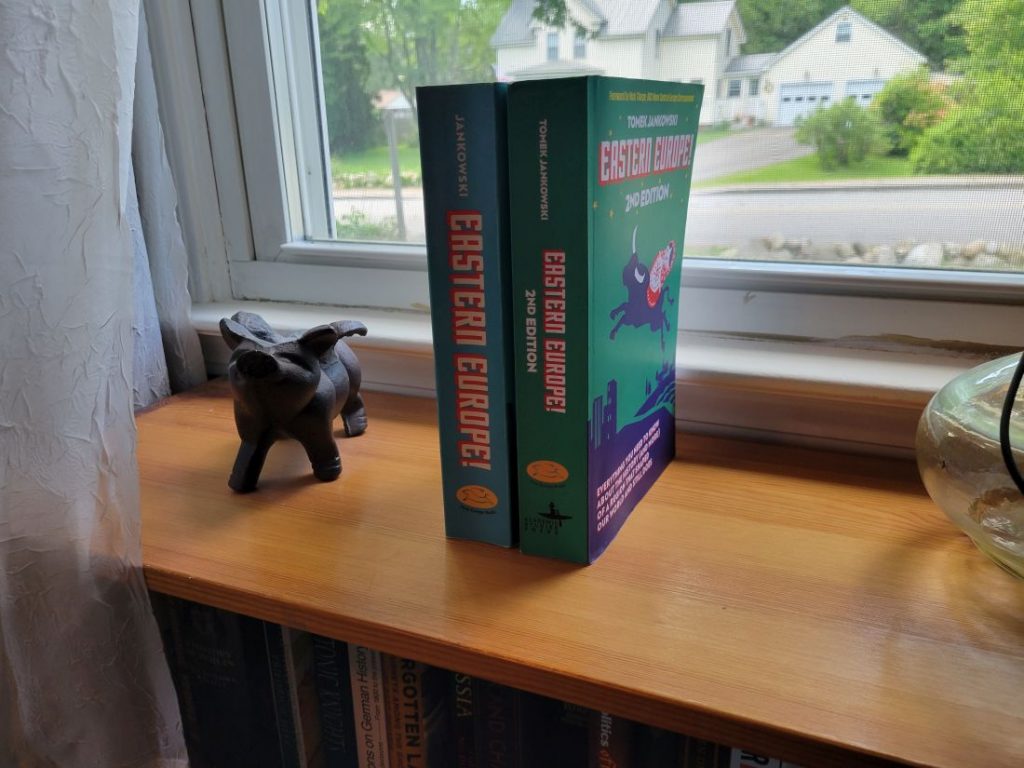

— Tomek

I’ll start with some local conditions chat, then get to the discussion. Two weeks ago here in New England, we got 3″ (about 8 cm) of snow, but since then we’ve had days where the temperature reached as much as 80 degrees F (27 C) — and it has rained. My backyard has jungle-ified to the extent that while working back there this morning, you could feel the flora breathing with the humidity. (I already have had to deploy the chainsaw to free some trees of vines.) My wife is also doing hand-to-paw combat with the chipmunk colonies. In short, spring is here.

I’ll start with some local conditions chat, then get to the discussion. Two weeks ago here in New England, we got 3″ (about 8 cm) of snow, but since then we’ve had days where the temperature reached as much as 80 degrees F (27 C) — and it has rained. My backyard has jungle-ified to the extent that while working back there this morning, you could feel the flora breathing with the humidity. (I already have had to deploy the chainsaw to free some trees of vines.) My wife is also doing hand-to-paw combat with the chipmunk colonies. In short, spring is here.